Innovation. The topic haunts me, and will likely continue to do so for a bit longer. It’s wonderful. It’s terrible. It’s a lot of things. The subject has gotten complicated, as the world tends to be. My concern is that fake innovation is distracting us from the good stuff. Maybe that’s the plan, but if so - it sure seems like a crap plan. Let me try to explain what I mean.

Having been paid for a number of years to play innovator (in addition to 3D printing specific innovation work I’ve been asked to evaluate any and all other manufacturing related innovations at some point) I have started to conclude that almost nobody calling the shots understands the subject these days. Or what they understand is only some limited aspect that tends to be dumb. I’m not sure that I understand innovation either, the way that things have been going in strange loops these days. There are quite a number of books on the topic, you can take courses on it, you can even be a VP or director of innovation in these wild times. So what are these innovation people doing exactly? Going to conferences, pushing for certain initiatives, buying equipment of dubious purpose - it all seems a bit odd to those working on the more normal side of corporate organizational life. The rest of the business, working hard to keep the numbers up and make money, casts aspersions and evil eyes at these chuckleheads being paid to find elaborate ways to spend the money they are making.

This isn’t MY opinion exactly, but I’ve seen the looks. There’s a larger argument to be made that the innovation economy entertains an elite delusion of sorts. What this planet cannot afford, is delusion among its decision-making class. Unfortunately, this seems to be the present state of affairs.

It makes one wonder: “why is this even happening?!” (Just don’t ask that question TOO much, it gets downright existential). I don’t quite know, but I have some guesses. Most of those guesses have to do with the innovation economy, which may have relatively little to do with innovation in the end. Confused yet? Me too, but I promise, we are going somewhere with this.

To further complicate the situation, innovation as a subject appears rather nebulous. At its simplest, it means doing something novel (unironically making something new under the sun).

On one hand innovations can be substantial and disruptive, changing human culture in a matter of months or years. Software and Apps seem to be particularly apt at this innovation supernova phenomenon. When real world data can be functionalized and acted upon systemically, big changes can happen quickly.

On the other hand innovations can often appear trivial or seemingly pointless - you can be innovative in the most mundane of areas of activity in a way that nobody wants to hear or think about unless they have a fondness for minutia and you find a way to tell a story around it like “This American Life” might do.

Somewhere in between these two extremes lie the majority of innovations. Because we tend to think in binaries, people want to put innovations into one of the two boxes, including better ways of doing something that aren’t massively disruptive, nor are they inconsequential. These ‘middling’ innovations - a better robot gripper, a more robust fixture, a more precisely fabricated induction coil, a faster method of prototyping, a more precise analytical method, a more accurate cost model - often represent improvements or advancements which may possesses benefits not limited to cost and time savings, possessing aspects which don’t package into a simple story which appeals to typical organizational logic. As the relative nature of disruptive or trivial innovations lie in the eye of the beholder, sometimes the important is dismissed.

When management needs to decide to fund or not fund something, the binary becomes unavoidable to get a bang for their bucks. Noting that the world is often ternary if not downright fuzzy and quantum, it’s not a surprise that we sometimes miss the mark. Everyone has their own thresholds for what constitutes making a meaningful impact.

In short - the vast majority of improvements and opportunities become invisible if management puts them into the trivial box, below their threshold of giving a damn. Seemingly few opportunities are good enough to be considered disruptive, especially if the decision maker is sufficiently abstracted from the context.

So innovations mean different things to different people, and they can have different degrees of impact as either a product, process, method, mentality, memeplex or other construct.

Okay, so if we pretend to understand innovations generally for the moment - None of this has much to do with the Innovation Economy. What is the Innovation Economy? Hard to say, exactly. It looks to be a bunch of startups, consultants, and assorted oddballs leaning heavily on a fun house of ideas. Ideas of various merit and demerit which seem to have a strong influence on some non-insubstantial portion of corporate discretionary spending, often through quixotic C-suite led innovation initiatives. What kind of initiatives? Well, usually things that get onto the ‘innovation checklist’.

You’ve heard of some of the innovation checklist, I assure you. Here’s a quick run down of typical checklist entries:

AI / ML / Neural Networks

Quantum Computing

Big Data / Data Analytics

Digital Twins / Digital Thread

Blockchain (sans Bitcoin, ofc)

Biohacking / CRISPR

Additive Manufacturing

Internet of Things / Industrial IoT / Factory 4.0

Collaborative Robots

Integrated Computational Materials Engineering

Electric Vehicles

(Insert novel buzz-phrase here)

Many of these topics have nothing wrong with them, and are worthy of support when a relevant problem arises. Some are almost complete nonsense. A few are sexy rebranding of things which are already being applied as opportunities and competence grow. Here’s the concern : the innovation checklist seems to be a psychological crutch that has a LOT of interest at an elite level of society. Board members care about these subjects. The C-suite cares about these subjects. The Military cares about these subjects. The investment class cares about these subjects, seemingly to the exclusion of many other target opportunities. Why is this? Just because “innovation = good”?

Pursuing the same set of subjects that everyone else thinks are innovative seems like some perverted form of ‘fake innovation’. It’s ironic innovation, perhaps, because at best these methods are being pursued exnovatively. This makes sense - leadership in corporate structures has generally been trained to exnovate intuitively. The real question then becomes “why are THESE topics on the checklist?”

There seem to be several reasons for this state of affairs.

One of the culprits seems to be a general disregard by most executive types for internal Engineering and R&D. The innovations done routinely by these groups have become commonplace, trivial, or simply invisible in many organizations - hidden amongst the weeds of every day operations. A smaller organization might allow the CEO go back through operations with a fine tooth comb to make sure they understood as much as they could about the business. They may have started it or grown up through it and learned everything going on in the company. In a larger organization this becomes both practically and culturally impossible, even if the founder is still around to dig. Absent smart local investments in the organization, how can decision makers then take their cash and innovate, or at least invest in something that becomes ‘the future’? What can one offer? You could offer them more traditional investments, but perhaps those seem a bit dubious these days too.

Instead of anything so bland as ‘what used to work for successful organizations’, a sexy science fiction future is being peddled, propped up by the innovation checklist. Who performs the peddling?

One of the main culprits for this is Singularity University, a weird think tank / feel good fest / proto cult, founded by Ray Kurzweil and Peter Diamondis. FWIW, I have no personal problem with either of these dudes. Never met them. Some of their ideas are even interesting, and it’s cool that they’re so successful at starting businesses though it’s not so clear how much of that success is up to novel ideas as opposed to being well connected. In any case, they are held in high regard as being visionary in some sense. I have a lot of respect for anyone who can hold a vision and execute on it, but vision alone can be downright goofy and disconnected from reality. It has to be. Being first and being crazy look remarkably similar, after all.

Here’s the issue: The vision of Singularity University intentionally or unintentionally creates a state of innovation fanaticism.

The mind-state of the innovation fanatic typically believes that small to medium size enterprises (SMEs) will be left in the dust if they don't frantically implement some or all of the innovation checklist. They are told that they MUST keep pace or they will be 'disrupted' and left in the dust. When this scare tactic works on the C-suite, they jump to engage some outside organization to help the SME to perform some activity in this area.

The C-suite may shell out for some Singularity University university event, because they didn't bother to do any homework on THAT goofy outfit. They will be pampered. They will have multimedia talks to listen to. They will have interesting demonstrations to look at. They will sample the Hors-d'œuvre. They may think: “Wow, maybe I should also freeze my body for subsequent scientific resurrection! Can I invest in liquid nitrogen as a commodity?” They’ll pick one of the innovation checklist topics that seems to be their favorite. Maybe it plays to their background or an interest of theirs. They may go on to hire someone who promises to sprinkle a little machine learning onto some favored program.

Often the target SME (the mark) shells out money to 'innovate’, typically to either A) some young startup with a smart sounding CEO who has no demonstrable capability or wins to their credit who will take the money to go pretend to do something or B) some established organization MUCH larger than the SME who will promise to sell some solution and support thereof who will take the money to go pretend to do something. In either case, the SME is often left holding the bag, with little to show for their investment.

(In most cases the real innovation seems to be in snake oil salesmanship methods… )

A second culprit, is the World Economic Forum. Apparently when someone talks about “those Davos people”, they are referring to anyone wealthy, well connected, or otherwise elite enough to participate in the WEF at some level. It’s a distinguished bunch, several of whom happened to pal around with Jeffrey Epstein, who also loved the innovation checklist. (Maybe he just smelled the money?)

The Founder of the WEF, Klaus Schwab, wrote a book about the fourth industrial revolution, contributing cred to Industry 4.0 and perhaps bumping it higher on the innovation checklist. The idea generally plays well with the ownership class because it promises the potential to fire most people while having robots do all the work. They assume that Robots don’t unionize, which seems true to first order but seems unaware that the designed obsolescence, constant licensing fees, digitalization of Murphy’s law, and other institutional snafus are an effective union of unholy forces which will never allow their hopes to be achieved.

The unstated mantra of the innovation space appears to be that technological innovation will save us. This seems to be a dubious assertion - it’s like nobody in the World Economic Forum ever watched Black Mirror. At some level some of the elite accept this and are aiming for escape - see Douglas Rushkoff’s experience for further detail. His follow up helps to explain the deeper rot of SU’s approach.

Once the money men buy into an idea, that idea gets legs. If it doesn’t have legs, robotic legs will be 3D printed for it, so that it may run headlong into the distance - or barring that into a brick wall of physical un-realism. The money is there either way, and they seem to have stopped checking for walls. This is the realization that helps to bring peace to the larger malpractice of innovation now ongoing: elite misunderstanding of technological development is exactly the kind of thing that might save humanity from being subject to their social engineering efforts!

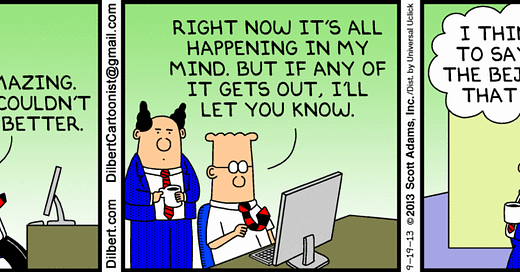

A number of observers have noted that innovation ain't what it used to be. There are some pretty compelling arguments that our general ability to engineer and problem solve has been degrading over the past 100 years. This problem is not for a lack of technology, if anything our technology now distracts us as often as it helps us solve problems. That said, part of the problem can almost certainly be pinned to organizational rot and incompetence at high levels, driving unproductive activity which masks itself as innovation through science fiction narratives which are somehow simultaneously elaborate and vague. Dilbert exists and lands an audience for a reason, after all…

So, yeah. I said that innovation haunts me, and perhaps now you have a feeling for why. Our present vision of the future isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, nor is it what our future will be. I hope you weren’t hoping for a happy ending or something uplifting here, I tried to tell you I don’t have answers to this predicament. What do? As victims of our own success, we may have lost sight of a potential set of solutions: pragmatic reasoning and common sense. Some are yet able to afford distracting fantasy over necessary reality.